ARTIST INTERVIEWS, OIL PAINTING

12th October 2022 by Clare McNamara

Robbie Bushe won the Landscape/Cityscape/Seascape Award in the Jackson’s Painting Prizethis year with his work Learney Incantation (Tornaveen). In this interview, artist and previous winner of the same award, Sarah Bold, asks Robbie about his practice, materials and finding inspiration in 1970s science fiction.

Sarah: First of all, can you tell us how you came to be a painter?

Robbie: My dad was a sculptor (formal, metal and wood, a bit like Anthony Caro) and Mum did performance, design, poetry and much more – she was brilliant. I was always going to have the arts in my spirit and I could draw. In my early years, I used this skill to imagine the world through stories and characters. I devoured British comic books such as 2000AD and Judge Dredd in the late 1970s, as much for their team of talented young comic artists as the social political satires set in the near future. I was fascinated by their use of scratchy dip pens and bold black and white ink artwork. I developed my own style and soon was creating my own comic strips which traded at school for sweets. I was heading for art school to be a comic book artist. However, when I got to Edinburgh College of Art, there was no comic book artist course, just very conventional illustration, which I had no interest in. But this was the 1980s and making a lot of noise in the west at Glasgow School of Art were the new Glasgow Boys; Steven Campbell, Peter Howson, Adrian Wiszniewski, and Ken Curry. They made bombastic and surreal narrative figurative paintings which felt a bit like new comic book art writ large. I was green-eyed but hooked. I studied painting at Edinburgh, which at the time favoured a decorative colourist and close tone approach from the ghosts of Anne Redpath and William Gillies. So, my work evolved from the overtly graphic figuration tempered by subtle brushwork of neutral and muted colours.

Sarah: Drawing seems to be a very big part of your practice and the foundation of your painting. Can you tell us how the drawing for a painting starts and how does it develop into a painting?

Robbie: Drawing is the scaffold I need to hang my paintings on. I have a dexterity with a pen I can only dream of with a brush. It has taken me the last 30 years to realise that one can serve the other – like the spaces between the beats and notes in music. These days not all my painting evolve or arrive in the same way. However, when I am starting a new body of work or working on a set of new ideas, I will usually do much of the following: Collect, cut out and paste images from newspapers and magazines or printed off the internet which broadly reflect some of the ideas I am thinking about. For a while that has been sprawling urban infrastructures, but right now its energy supplies, pipelines, border crossings, invasions, popularism and gardens. I am interested in civil and social engineering as a contrivance for commentary in my work. I will paste these images randomly through a drawing book leaving lots of white space. Over time I open a page and draw around them joining them up, expanding them and inventing figures and stories. I do these best when I am almost daydreaming, at work meetings, watching tv or listing to a podcast. At the same time, I will be making observational drawings which may or may not connect with the ideas I am playing with but somehow, I will eventually allow them to submerge with what I have been thinking about. Right now, it’s my own garden which has become a creative stage set for my work. Eventually these drawings, mostly using fine liner pens, start to develop into compositional thumbnails drawings which could become small- or large-scale paintings. They give me confidence to improvise and riff off the ideas and motifs which seem the most compelling. Eventually I will pluck up the courage to start the building process of my paintings.

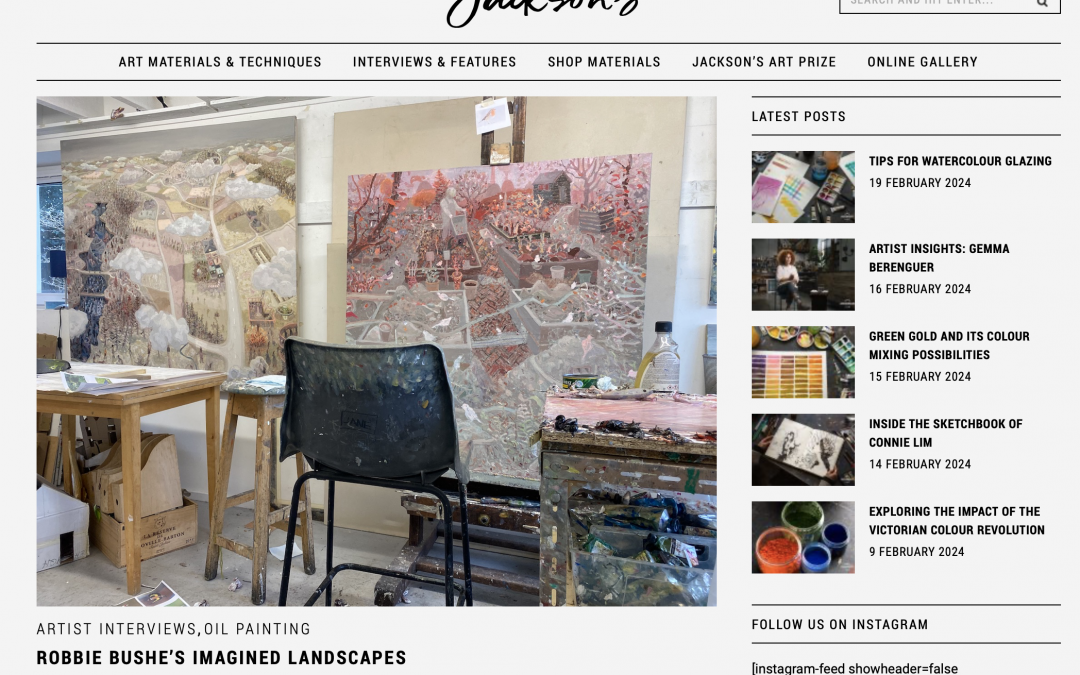

Robbie in his studio space, 2021

On my large-scale work this starts on sized canvas – rather than gesso primed. I like to start paintings using fine coloured pens for the armature-like exploratory drawing and sized canvas remains smooth enough for this, to help me build up a mesh of exploratory lines from lighter to darker tones as the drawing evolves. While it looks structural and detailed it is born from a free-flowing approach not dissimilar to how I improvise in my drawing books. I love what an expanded scale does to my images and spaces to create panoramas with complexity. It is only when I can see the whole image and have reference to each bit, whether it be a building, table, tree, or vehicle do I feel confident to start painting. It may be too simplistic to say that I proceed to ‘colour in’ the drawing but would be pretty accurate. I may often start with a specific colour palette in mind and somethings I will create a mood board to give me guidance on the colour, tone, and mood for the work. Next stage is deciding what passage I am going to paint and then spend up to an hour mixing up enough oil paint. If the range of colours and tones look good on the palette, they have a fighting chance of looking good in the painting. Colour balance and close tones is an important part my painting. So, drawing done, paint mixed – now I feel confident to paint. Despite the detail and complexity of my drawing, I cannot keep my hand still with a brush, but I have learned not to protect the drawing underneath and allow the paint to sit not quite in the right place. The viewer is always aware of the under-drawing, but it is this combination of line and paint which has allowed my work to develop and become distinctive for now – but my approach is always evolving.

Sarah: Will you do numerous drawings first or draw directly onto the canvas? What is your process?

Robbie: I am always drawing – mostly in my books but often on meeting agendas or notes for work. If there is a lot at stake as in a large work, I make numerous thumbnail drawings of possible compositions for an idea – seldom do these leading to a definitive one and I still prefer the discovery of drawing straight onto the canvas with a degree of improvisation.

A Scottish Goldmine, 2022

Robbie Bushe

Oil on canvas (in two panels), 140 x 260 cm | 55 x 102 in

Sarah: Do you have a preferred scale to work to and why this works best for you?

Robbie: It really depends on where I am in the cycle of a body of work. I recently completed a series of 14 small paintings. This allowed me to work on several at once, letting me work ideas out and allow one painting to help another. I have a short concentration span – I usually only paint in two-hour bursts – so this is a useful ploy at the start of series. Right now, I have four large canvasses ready to get start on for the winter. If I have planned it right and the ideas in the paintings mean enough to me and I have explored and researched thoroughly, then getting lost in these paintings over the coming months will be heaven. I like to know what my plan is when I arrive in my studio – just a hop out of my house into the garden.

John Moores entry work in Progress, 2019

Sarah: There is so much to see in your paintings, they are very absorbing. Can you explain about the narrative? Where do you get your inspiration?

Robbie: This has evolved quite a bit over the years. In my early career I was known more for paintings of large figures within domestic interiors or rural locations – often autobiographical, stories of my family, breakups, and broken dreams. But eventually I ran out reasons to make these works and they got a little irrelevant.

About ten years ago, having felt I had lost my focus as an artist, I set about rebuilding my practice and what I would make my work in response to. I started by ensuring I made a new complete pen drawing in my book every day. I did this and little else for a couple of years and nothing was off limits subject matter-wise. If I wanted to add a ‘Daleks into a Italian panoramic landscape’ I allowed myself. Some drawings were from life, often around the hills a cityscape of Edinburgh, others were from invented or remembered places where I could run riot with mining my own past and dormant interests. These included civil engendering, bridges, road structures and networks, cutaway illustrations of factories and ships (and space-ships). The more I dipped into my own memories the more I was able to reconstruct whole buildings and interiors space through my daily drawings, allowing myself the permission to follow and record all these trails. Eventually they came out in the paintings, but it took some time to figure out how and why, but it gave me far more visual tools and motifs to allow ideas and positions on the world to take shape.

Robbie with Stanley in his Studio.

Sarah: You have grown up in very beautiful Scotland, amongst many places. Does the Scottish landscape influence your work in anyway? Are your paintings specific to a single place or more of a collection of places?

Robbie: I have lived in Liverpool, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Chichester, Hastings, Oxford and Edinburgh where I returned to in 2007. All have had an impact on the images in my work, but rarely do I make a work which is a specific location. I often see part of my job as a bit like a movie location hunter – find a place to tell a story or reveal an idea. There is no doubt that panoramas of Edinburgh, its hills, rocks and layered city, play a huge role in defining how I reveal space and distance.

The Road Builder, 2021

Robbie Bushe

Oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm | 55 x 47 in

Sarah: Looking at your paintings is like peeling back a layer of skin, particularly the open houses. I have the feeling of peering through a window, almost on the sly – observing from a hidden space complex lives that feel both familiar and fairy-tale at the same time. Would you say that your paintings are similar to a biography of your life in some way? How much is from personal experience and reality compared to imagined?

Robbie: The peeling back comes from my renewed interest in the art of the ‘cut-away’ I became aware of in the pages of Look and Learn in the 1970s but harks back to engineering drawing through the industrial revolution to today’s industrial design virtualisations. The device allows me to show what is happening to the inside of buildings while revealing their context with the landscape or urban setting. I have so much fun with that, but when I started to paint from memory images of some of the many homes and locations, I have lived then it did become more autobiographical – not retelling stories and to take me back to places and add to the memory. The remembered and imagined become completely entwined. I found it cathartic to retrace steps and figure out the lay-out of a building I had once lived and getting it wrong is all part of the process, reshaping my memories.

Neanderthals Futures Infirmary, 2019

Robbie Bushe

Oil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm | 63 x 40 in

Sarah: You have mentioned 1970’s science fiction tv is sometimes a recurring theme – why is this so?

Robbie: I was obsessed with science fiction from the moment I hid behind the sofa from the yeti in Doctor Who the late 1960s. I devoured tv, film and comic books. It was the visuals, character and the monsters which I could draw, role play and get lost in my own world in rural Aberdeenshire in the 1970s. I would not have dared to introduce any hint of this my work in the early years of my career. It was only more recently that I started to mine my memories and early obsessions in my work. I never imagined the world would return in my lifetime to be such a volatile and unstable place. The politics of now and the sci-fi of my yesteryears seem good bedfellows to rehearse and reveal some of these ideas and my positions on them.

Youth Theatre, 2021

Robbie Bushe

Oil on canvas, 87 x 101 cm | 34 x 40 in

Sarah: Your work is very detailed, have you always painted in this way?

Robbie: I have developed the ability through my early comic book aspirations to draw quickly and be able to expand ideas over a page. Painting in this way came much later as I tried to find ways to enable to same dexterity. My brushwork was plodding and messy and I could never envision a way to get the kind of detail I can in my drawing. I would just settle for a clean edge and a sense of light. It took many years for my understanding on how to use and apply painting which complimented my drawing.

Tenement Alimentation, 2020

Robbie Bushe

Oil on panel, 100 x 81 cm | 40 x 32 in

Sarah: Many artists talk about happy accidents in the studio that come from experimentation. How do you experiment within the studio and if so what sort of thing will you try?

Robbie: I am always a bit wary on this one. Some artists talk about the ‘happy accident’ as if it is a deliberate part of their process. But the danger is that these accidents can feel contrived and without reason. I allow experimentation and playful wiggle room at each stage of my processes, but their needs to be a core rigour and purpose running though my work. Yes, sometimes things happen or occur during the process which is unexpected or unplanned and you have to make a decision whether to run with it or not. But it’s not an accident, it’s part of the process of making art – responding and adjusting.

The Blowtorch Incident (Tornaveen), 2021

Robbie Bushe

Oil on canvas, 101 x 87cm | 40 x 34 in

Sarah: Do you have a favourite colour palette that you return to? Favourite colours that you use most?

Robbie: I seem to always return to the Yellow, Ochre, and Grey Close tone palette as I find it calming and familiar – a haven when I am not sure of the composition. I actively try to extend my range and I do this using a mood board or following the colours from a photograph I have selected. I have become much more equipped and confident mixing colour over the years. I use prefer oils and I need to be able to spend a good hour colour mixing and enjoying the colour swatches appear on my palette.

Sarah: What do you find most challenging within your practice? What do you do if you feel a painting isn’t working? What do you enjoy the most?

Robbie: I work 4 days a week as an art lecturer at the University of Edinburgh so carving out enough time to make work is always my biggest challenge. I have learned way weave my practice around my life and work commitments and am able to take the opportunities of a free hour to draw or get to the studio. Little and often.

Clare McNamara

As Blog Editor, Clare oversees content for the blog, manages the publishing schedule and contributes regularly with features, reviews and interviews. With a background in fine arts, her practices are illustration, graphic design, video and music.